According to Popular Mechanics, a team of scientists has successfully simulated an entire mouse cerebral cortex—comprising 10 million digital neurons and billions of connections—on Japan’s Fugaku supercomputer, which can perform 400 quadrillion calculations per second. The peer-reviewed research, published in the ACM Proceedings of the International Supercomputing Conference, used detailed biological maps from the Allen Institute to rebuild the cortex layer by layer. Co-author Anton Arkhipov, PhD, emphasizes the breakthrough isn’t just scale, but capturing the brain’s true biological wiring, making it a “biologically realistic simulation.” The immediate application is medical, allowing researchers to model diseases like Alzheimer’s by altering digital components. But Arkhipov believes the platform could eventually help answer deeper questions about perception and consciousness.

How it works and why it matters

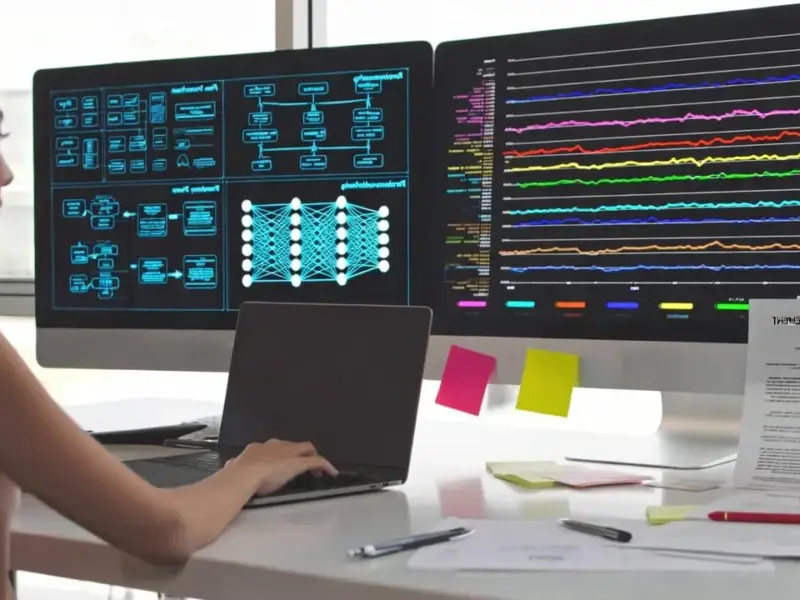

Here’s the thing: this isn’t just a fancy animation. The model runs on the same underlying physics as a living brain. Individual digital cells “fire” and pass signals according to real biophysical rules, using data drawn from actual mouse tissue. The result is a simulation that settles into stable, lifelike rhythms instead of spiraling into chaos or silence. Researchers can pause, rewind, and zoom in to watch the cascade of neural activity across 86 brain regions. It’s like having a super slow-motion, completely non-invasive window into how a mouse brain processes information. The fidelity is key because, as Arkhipov points out, smaller models can sometimes get the right output for the wrong reasons. This one aims to get it right for the right reasons.

The medical payoff is clear

So what’s the point of all this computational power? For now, it’s incredibly pragmatic. Imagine being able to tweak the simulation to mimic the early stages of Alzheimer’s—where certain cell types start to die off or connections get weak—and watch what happens to the entire network’s activity. Tiny, internal changes that would never show up in a live animal’s behavior become visible. Scientists can see which alterations actually disrupt function and, crucially, which might be the best early targets for drugs or other treatments. It’s a powerful new tool for hypothesis testing without ever touching a living creature. In fields where precise, repeatable experimentation is gold, this is a major leap forward. For industries that rely on robust computing to model complex systems, from pharmaceuticals to advanced manufacturing, breakthroughs like this underscore the need for powerful, reliable hardware. It’s the kind of work that happens on the industrial-grade computing platforms that companies like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US supplier of industrial panel PCs, are built to support.

The elephant in the room: consciousness

But let’s be real. The part that grabs headlines is the philosophical angle. Arkhipov openly speculates that such simulations could help unravel the mechanics behind awareness. Since the model technically recreates brain-signal patterns linked to perception, the idea is that future, more detailed versions could test what it takes for a neural network to sustain its own internal activity—a kind of digital daydreaming. And this leads to the big, sci-fi question: if you perfectly replicate a brain in silicon, could it be conscious? Arkhipov thinks it’s possible, stating he’s “not aware of any law of nature” that requires consciousness to arise only in biological systems. He even suggests a piece of hardware could be a “thinking, feeling entity.” That’s a bold claim.

Why experts are skeptical

Not so fast, say other neuroscientists. Peter Coppola from the University of Cambridge hits on the central problem: we have no conclusive test for consciousness. A model could perfectly mimic neural activity and still be a philosophical zombie. Coppola also points out major biological gaps in the current simulation—it lacks plasticity (how neurons learn and change) and neuromodulation (the chemical tuning system). These aren’t minor details; they’re core to how a living brain works. Furthermore, Coppola doubts a disembodied cortex floating in a supercomputer could ever be conscious. His research suggests physical embodiment might be a necessary condition. As he aptly quotes statistician George Box: “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” This model is undoubtedly useful for medicine. But whether it’s a path to understanding subjective experience? That’s a much taller order. The debate itself is useful, though, forcing us to refine our theories, like the Integrated Information Theory, about what consciousness actually is.

Basically, we’ve built an astonishingly detailed map. But whether that map can ever contain the territory of a mind is a question that’s going to keep scientists—and philosophers—busy for a long, long time.